<펌> Romanos II ( r 959-963)

2022. 7. 1. 01:42ㆍ역사 자료/비잔틴제국 (867-963)

Romanos II

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Jump to navigation Jump to search

Romanos IIByzantine emperorReignCoronationPredecessorSuccessorCo-emperorsBornDiedSpouseIssueDynastyFatherMother

| Emperor and Autocrat of the Romans | |

|

Gold solidus with Romanos II and his father, Constantine VII

|

|

| 9 November 959 – 15 March 963 |

|

| 6 April 945 as co-emperor | |

| Constantine VII | |

| Nikephoros II | |

| Constantine VII (945–959) Basil II (960–963) Constantine VIII (962–963) |

|

| c. 937 | |

| 15 March 963 (aged 25–26) | |

| Bertha of Arles Theophano |

|

| Basil II Constantine VIII Anna Porphyrogenita |

|

| Macedonian | |

| Constantine VII | |

| Helena Lekapene | |

Romanos II Porphyrogenitus (Greek: Ρωμανός, c. 937 – 15 March 963) was Byzantine Emperor from 959 to 963. He succeeded his father Constantine VII at the age of twenty-one and died suddenly and mysteriously four years later. His son Basil II the Bulgar slayer would ultimately succeed him in 976.

Life

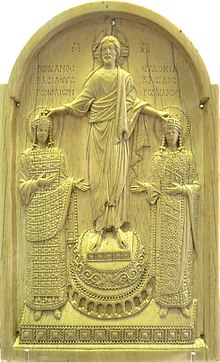

Known as the "Romanos Ivory", this carved plaque is thought by some scholars to represent the marriage of Romanos II and the child bride, Bertha/Eudokia being blessed by Christ.

Romanos II was a son of the Emperor Constantine VII and Helena Lekapene, the daughter of Emperor Romanos I Lekapenos and his wife Theodora.[1] Named after his maternal grandfather, Romanos was married, as a child, to Bertha, the illegitimate daughter of Hugh of Arles, King of Italy to bond an alliance. She had changed her name to Eudokia after their marriage, but died an early death in 949 before producing an heir, thus never becoming a real marriage, and dissolving the alliance.[2]

On 27 January 945, Constantine VII succeeded in removing his brothers-in-law, the sons of Romanos I, assuming the throne alone. On 6 April 945 (Easter), Constantine crowned his son co-emperor.[3] With Hugh out of power in Italy and dead by 947, Romanos secured the promise from his father that he would be allowed to select his own bride. Romanos chose an innkeeper's daughter named Anastaso, whom he married in 956 and renamed Theophano.[citation needed]

In November 959, Romanos II succeeded his father on the throne amidst rumors that he or his wife had poisoned him.[4] Romanos purged his father's courtiers of his enemies and replaced them with friends. To appease his bespelling wife, he excused his mother, Empress Helena, from court and forced his five sisters into convents. Nevertheless, many of Romanos' appointees were able men, including his chief adviser, the eunuch Joseph Bringas.

The pleasure-loving sovereign could also leave military matters in the adept hands of his generals, in particular the brothers Leo and Nikephoros Phokas. In 960 Nikephoros Phokas was sent to Crete with a fleet that was considered by contemporary historians as notably large, but probably not comprising more than 25,000-30,000 soldiers and sailors in total.[5] After a difficult campaign and nine-month Siege of Chandax, Nikephoros successfully re-established Byzantine control over the entire island in 961. Following a triumph celebrated at Constantinople, Nikephoros was sent to the eastern frontier, where the Emir of Aleppo Sayf al-Dawla was engaged in annual raids into Byzantine Anatolia. Nikephoros took Cilicia and even Aleppo in 962, sacking the palace of the Emir and taking possession of 390,000 silver dinars, 2,000 camels, and 1,400 mules. In the meantime Leo Phokas and Marianos Argyros had countered Magyar incursions into the Byzantine Balkans.

Death of Romanos II

After a lengthy hunting expedition Romanos II took ill and died on 15 March 963.[6] Rumor attributed his death to poison administered by his wife Theophano, but there is no evidence of this, and Theophano would have been risking much by exchanging the secure status of a crowned Augusta with the precarious one of a widowed Regent of her very young children.

Romanos II's reliance on his wife and on bureaucrats like Joseph Bringas had resulted in a relatively capable administration, but this built up resentment among the nobility, which was associated with the military. In the wake of Romanos' death, his Empress Dowager, now Regent to the two co-emperors, her underage sons, was quick to marry the general Nikephoros Phokas and to acquire another general, John Tzimiskes, as her lover, having them both elevated to the imperial throne in succession. The rights of her sons were safeguarded, however, and eventually, when Tzimiskes died at war, her eldest son Basil II became senior emperor.

Family

Romanos' first marriage, in September 944,[7] was to Bertha, illegitimate daughter of Hugh of Arles, King of Italy, who changed her name to Eudokia after her marriage. She died in 949, her marriage unconsummated.[8]

By his second wife Theophano he had at least three children:

- Basil II, born in 958[1]

- Constantine VIII, born in 960[1]

- Anna Porphyrogenita, born 13 March 963

See also

Notes

- Reuter & McKitterick 1999, p. 699.

- Ostrogorsky, George (1968). History of Byzantine. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. pp. 283. ISBN 0-8135-0599-2.

- Skylitzes, John (c. 1057). Synopsis of Histories. Translated by John Wortley. Cambridge University Press. p. 228. ISBN 9780511779657.

- Gibbon, Edward (1904). The Rise and Fall of the Roman Empire. Vol. V. According to Gibbon, "after a reign of four years, she mingled for her husband the same deadly draught which she had composed for his father.". London: Ballantyne, Hanson & CO. p. 247.

- McMahon 2021, p. 67-69.

- Georgius Cedrenus − CSHB 9: 344: "Anno mundi 6471 mortuus est Romanus imperator, 15 die Martii mensis. indictione 6, annos natus 24. imperavit annos 3, menses 4, dies 5." [10 November 959 − 15 March 963]

- Theophanes Continuatus records the marriage in September 944 of "Hugonem regem Franciæ...filiam" and "Romanus imperator...Romano Constantini generi sui filio", stating that she lived five years with her husband, although he confuses the identity of Bertha's father. Theophanes Continuatus, VI, Romani imperium, 46, p. 431.

- Byzantine historian George Kedrenos recorded that that "filia Hugonis", married to "Romano", died a virgin. Liudprandi Antapodosis III.39, Monumenta Germaniæ Historica Scriptorum III, p. 312.

References

'역사 자료 > 비잔틴제국 (867-963)' 카테고리의 다른 글

| <펌>Constantine Lekapenos (co-emp, r 924-945) (0) | 2022.07.01 |

|---|---|

| <펌> Stephen Lekapenos (co-emp, r 924-945) (0) | 2022.07.01 |

| <펌>Christopher Lekapenos ( Co-emp, r 921-931) (0) | 2022.07.01 |

| <펌>Constantine VII ( r 913-959) (0) | 2022.07.01 |

| <펌> Alexander (Byzantine Emperor, r 912-913) (0) | 2022.07.01 |