Definition

Throughout the 9th century CE, Viking raids on the region of Francia (roughly modern-day France) increased in frequency, destabilizing the region, and terrorizing the populace. The raids seem to have been inspired by the death of the Holy Roman Emperor Charlemagne in 814 CE or, at least, correlated with it. Charlemagne (king of the Franks, 768-814 CE; Holy Roman Emperor, 800-814 CE) had led numerous military campaigns on Saxony during the Saxon Wars (722-804 CE), slaughtering thousands, and seemed invincible in battle. The Saxons appealed to the Danes for help and Denmark did what it could.

As long as Charlemagne lived, however, they had little hope of success but after his death there was no real challenge to Danish incursions. The first Viking raid to strike Francia via the Seine came in 820 CE and more would follow, the most dramatic being the Siege of Paris in 845 CE and 885-886 CE. The first of these, in which the Norse chieftain Reginherus (one of the possible inspirations for the legendary Ragnar Lothbrok) was paid handsomely by Charles the Bald (r. 843-877 CE) to leave the city, encouraged more; the second, after which the Viking Chieftain Rollo (l. c. 830 - c. 930 CE) remained in the land to raid the countryside, resulted in the Treaty of Saint Clair sur Epte in 911 CE, granting Rollo the land which would become Normandy (land of the Norsemen) in exchange for his protection against any future Viking raids. After 911 CE, although Viking bands still made incursions into West Francia, Rollo protected Paris and the surrounding area as he had promised and the Viking raids on Paris and its environs ended.

Charlemagne & the Saxon Wars

Charlemagne spent the greater part of his reign in military conquest, consolidating his power and that of the church. His campaigns against the people of Saxony were especially brutal and epitomized by the Massacre of Verden in 782 CE when he had 4,200 Saxons executed; an event remarked on even by his own Frankish historians who struggled to cast it in a positive light.

THE FIRST VIKING RAID IN FRANCIA CAME IN 820 CE WHEN 13 SHIPS MADE THEIR WAY UP THE SEINE & PUT ASHORE.

Prior to the Saxon wars, the Danes and Franks were acquainted through trade and there is no evidence of military conflict. During the wars, however, the Saxon chief Widukind asked for assistance from the Danish king Sigfried who agreed to allow Saxon refugees fleeing from Charlemagne's army into his kingdom. Charlemagne put a stop to this in 798 CE but when Saxony was conquered in 804 CE, the Danish king Godfred attacked and ably took Frisia from the Franks. Charlemagne was mounting an expedition to drive his forces out when Godfred died and his successor quickly sued for peace and withdrew.

The ease with which Godfred had been able to subdue Frisia, the lure of the wealth of the Franks, and possibly the need to avenge those killed in the Saxon Wars, encouraged other Scandinavian leaders to try their hand at invading Francia. Scholar Janet L. Nelson writes:

The aristocracy whom Godfred raised up had acquired an appetite for status and wealth. [After his death] temporarily disappointed men were driven to recoup their losses elsewhere. And where better than in the Frankish empire? In the generation or so after Charlemagne's death in 814, the amount of visible, readily available Frankish wealth continued to grow. (Sawyer, 22)

The first Viking raid came in 820 CE when 13 ships made their way up the Seine and put ashore. The raiders had no idea what to expect, however, and were quickly defeated by the shore guard. The survivors retreated to their ships and withdrew. Charlemagne had been succeeded by his son Louis I (the Pious, 814-840 CE) whose reign continued the prosperity and stability of the region and who held the Vikings at bay through bribes and favors; but upon his death his three sons vied with one another for control and the region devolved into civil war.

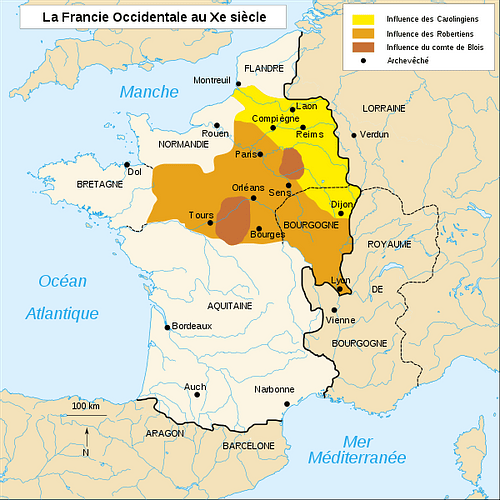

These wars were finally concluded by the Treaty of Verdun of 843 CE which divided the empire between Louis I's sons. Louis the German (r. 843-876 CE) received East Francia, Lothair (r. 843-855 CE) took Middle Francia, and Charles the Bald would rule West Francia. None of the brothers were interested in helping the others in any way and each would, to greater or lesser degrees, be left to deal with Viking raids on their kingdoms on their own.

The Siege of Paris 845 CE

The first significant Viking raid came in May of 841 CE, a year after Louis I's death, when the Viking chief Asgeir sacked and burned Rouen and looted the Monastery of Fontenelle and the Abbey of Saint-Denis. The amount of plunder and the number of captives taken was significant. Those prisoners whose families or friends could pay the Vikings a ransom were returned; the others were sold as slaves. Asgeir left the region a wealthy chieftain and this encouraged Reginherus to try for an even greater prize than Rouen: the city of Paris.

The Annals of Saint-Bertin (c. 840-880 CE), which record the Viking raids, names the leader of the 845 CE siege of Paris as Reginfred or Reginherus, who is only known for this one raid. Reginherus arrived with a fleet of 120 ships in late March of 845 CE and made his way up the River Seine toward Paris. Charles the Bald assembled an army quickly and mobilized them on either side of the river to protect the city but the two divisions were unequal in number.

Reginherus drove his ships against the smaller force, defeated them, and hanged 111 of the survivors. As there was no bridge across the Seine at this point, the rest of Charles' army could do nothing to stop Reginherus and he sailed on to Paris, reaching the city on Easter Sunday. This seems to have been according to plan as the Vikings understood the most valuable loot – and citizens – would be in church and easily taken.

Charles directed his army to save the Abbey of St. Denis, leaving Paris to fend for itself. News of the Viking's approach had reached the city, however, and when Reginherus arrived he found most of the population had fled along with their valuables. Scholar Lars Brownworth writes:

The city itself proved to be [frustrating for the Vikings]. Much of the expected treasure had been carried away into the surrounding countryside by the frightened inhabitants. They could send out raiding parties in search of it but that opened them to the possibility of ambush or an assault by Charles' army. In fact, every moment [Reginherus] spent in Paris, his situation worsened. The Frankish king had been collecting reinforcements, and was now at the head of a considerable army in a position to block the Viking escape. Even more worrying was the fact that the Vikings were beginning to show signs of dysentery, which further reduced their fighting ability. (48-49)

Reginherus sent emissaries to Charles indicating he was open to negotiations. Instead of refusing this request and pressing the obvious advantage he had, Charles agreed to pay the Viking chief 7,000 pounds in gold and silver to leave the city and, further, allowed him and his men to keep whatever they had taken from Paris. It took two months for Charles to raise the money, during which time the Vikings suffered from dysentery within and around the walls of Paris. The Parisians claimed this was divine retribution sent by Saint Germain of Paris (c. 496-576 CE), former bishop of the city, whose relics were housed in the abbey of Saint-Germain-des-Pres which Reginherus had attacked. More Vikings died from dysentery in the raid on Paris than in any form of combat.

Once Reginherus had been paid, he made his way back down the Seine – burning and looting as he went – and back home to present his victory, captives, and other spoils to King Horik of Denmark. He is said to have broken down in tears during his audience with the king and claimed that the only resistance he met from the Franks was in the form of the long-dead saint who had killed so many of his men in the city and on their way home.

THE 845 CE SIEGE ALMOST CERTAINLY ENRICHED RAGNAR BUT ITS LASTING SIGNIFICANCE WAS THE PRECEDENT SET BY CHARLES THE BALD OF PAYING A VIKING LEADER OFF FOR PEACE.

Horik had earlier sent a fleet of ships up the River Elbe to attack East Francia, burning and sacking Hamburg, but failing to achieve his objectives. Horik's men had burned churches and monasteries in Hamburg just as Reginherus had attacked the abbey of St. Germain and of St. Bertin in West Francia and news of the Frankish saint's alleged intervention was hardly welcome. Further, emissaries from Louis the German were in Horik's court when Reginherus made his presentation and they were quick to capitalize on the story, warning Horik of an impending invasion by Louis the German, no doubt backed by their own saint's supernatural power, if he did not submit to East Francia as a vassal.

Horik agreed quickly with the terms and “sent envoys to Louis the German with an offer to release all the captives taken by the invaders of 845 and promised he would try to recover the stolen treasure and return it to its rightful owners” (Ferguson, 96-97). Fearful of further reprisals by the Frankish saint, Horik had all of Reginherus' men he could lay hands on executed, though Reginherus himself escaped as did many of his warriors who had already left Denmark with their loot.

The 845 CE siege almost certainly enriched Reginherus and those of his men who survived it but its lasting significance was the precedent set by Charles the Bald of paying a Viking leader off for peace. Charles' deal with Reginherus marks “the first recorded example of the danegeld payment, a money-with-menaces tactic that the Vikings would later employ with great success in England” (Ferguson, 96). Once the memory of Saint Germain's supposed retribution faded from Viking memory, the large sum paid to Reginherus encouraged others to strike at the regions of Francia.

The Siege of Paris 885-886 CE

The Vikings were back in the region in 851-852 CE under the leadership of Asgeir who looted and plundered at will from a base they established at Rouen. Charles the bald alternately fought or tried to negotiate with the raiders but with little success. In c. 858 CE Bjorn Ironside, supposed son of Ragnar Lothbrok, and the Viking chief Hastein (also known as Hasting) burned the Abbey of Fontenelle and captured the monasteries of Paris, holding them for ransom until paid by Charles. In 860 CE, Charles contracted with the Viking Chieftain Veland to fight for him against other Viking bands in exchange for 3,000 pounds in silver and Veland worked, with more or less success, to secure the lower Seine region.

Still, the raiders kept coming and in 876 CE a fleet of 100 ships sailed up the Seine to burn and loot the region around Rouen. It is probable that Rollo was involved in this raid, if not its leader, and Charles was again helpless in preventing the Vikings from plundering the land and taking people captive to either sell or ransom back. The Viking rampage only ended when Charles paid them 5,000 pounds silver to go home.

The Kingdom of West Francia under Charles the Bald, therefore, became an easy source of income for the Vikings. If, as in the raids of 851-852 CE, they found little worth plundering in the ravaged countryside and communities, they could simply range a bit farther afield until the king paid them to leave. Scholar Robert Ferguson comments:

It seems obvious now that policies of appeasement and alliance with individual Viking leaders only encouraged them to push harder. The tactics employed by Louis the Pious, Lothar, Charles the Bald, and Charles the Fat established clear precedents for the gift of lands around Rouen and the lower Seine…Even so, it is hard not to sympathize with them, in particular with the two Charleses who made the most active use of the policy, or to see what alternatives they had. (104)

In 885 CE the Vikings returned to Paris. Following the death of Charles the Bald in 877 CE, the throne was held by his successors until the last one died in 884 CE without an heir and the nobles of West Francia invited Charles the Fat (youngest son of Louis the German) to reign. Charles the Fat was involved in his own affairs in East Francia and, besides, was not inclined toward military engagements. When the Vikings came up the Seine, defense of the city was in the hands of Odo, Count of Paris (later King of West Francia, 888-898 CE) who would become the Frankish hero of the siege of 885-886 CE.

The monk Abbo of Saint-Germain-des-Pres (9th century CE) gives the Viking leader's name as Sigfried but other sources cite Rollo as participating in this raid if not leading it. Abbo describes the arrival of the Viking fleet as seen from the walls of the city:

The Northmen came to Paris with 700 sailing ships, not counting those of smaller size which are commonly called barques. At one stretch the Seine was lined with vessels for more than two leagues, so that one might ask in astonishment in what cavern the river had been swallowed up, for nothing was visible there, since ships covered that river as if with oak trees, elms, and alders. (Sommerville & McDonald, 202)

Abbo relates how Sigfried met under truce with the bishop of the city, Gauzelin, and Count Odo to offer them terms but these were rejected. The next morning the assault on Paris began when the Vikings attacked the tower and bridge across the Seine which had been built to defend against raids following Reginherus' siege in 845 CE. The tower was defended by Frankish troops led by Odo and his younger brother Robert (later Robert I, r. 922-923) and held; the Vikings were driven back to their ships. The Franks spent the night repairing damage to the tower's walls and, in the morning, the Vikings struck again and were again repelled.

Unable to take the tower or breach the city walls, the Vikings settled in for a long siege. Abbo writes:

Meanwhile Paris was suffering not only from the sword outside but also from a pestilence within which brought death to many noble men. Within the walls there was not ground in which to bury the dead. Odo, the future king, was sent to Charles, emperor of the Franks, to implore for help for the stricken city. (Sommerville & McDonald, 223).

Charles arrived to relieve the city in 886 CE but, instead of engaging in battle, paid the Vikings to leave and suggested they go ravage Burgundy instead of West Francia. The Vikings accepted the money and did as he proposed but the people of Paris were disgusted with Charles' tactic. He was deposed and Odo became king in his place. Odo would reign for the next ten years until he was asked to step down in favor of Charles the Simple (r. 893-923 CE), grandson of Charles the Bald. Charles was crowned king in 893 CE by the West Francia nobles but held no real power as long as Odo was still king. The nobility pressured Odo to relinquish his reign and he steadily lost power but died before it could be taken from him; Charles then took the throne without opposition in 898 CE.

Rollo & the Treaty

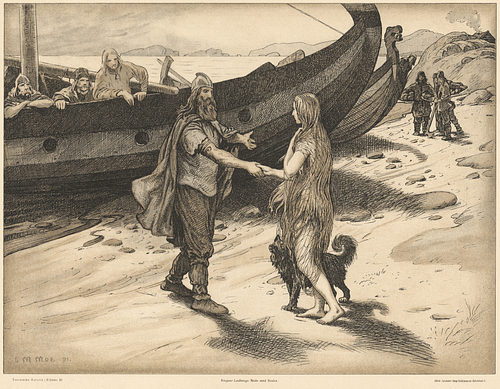

Following the Siege of Paris 885-886 CE, Rollo remained in West Francia raiding up and down the Seine. Commanders under Charles the Simple made some gains in 897-898 CE in defeating the Vikings but they could not dislodge them or stop the raids. Recognizing that there was no hope of military supremacy over his opponents, Charles proposed a deal to Rollo: the Viking chief would receive land and the king's daughter, Gisla, as a bride in exchange for converting to Christianity and becoming Charles' faithful vassal and protector of the realm.

Clive Standen as Rollo of Normandy

Jonathan Hession (Copyright, fair use)

Rollo agreed to this proposal and the Treaty of Saint Clair sur Epte was signed in 911 CE. True to his word, Rollo became the king's champion and Viking raids up the Seine on the surrounding countryside were ended. Rollo rebuilt the communities destroyed in earlier raids, instituted more effective laws, and joined Charles on campaign later to restore order in other regions and then to help him keep his throne when he was threatened (and later deposed) by Robert I in 923 CE. Rollo resigned as ruler of Normandy in 927 CE, dying in c. 930 CE and Charles would remain in captivity until his death in 929 CE but each man would leave behind a legacy of stability and freedom from Viking raids in West Francia for the first time since the reigns of Charlemagne and Louis the Pious.

The Raids in Vikings & Legacy

The Viking raids on Paris are depicted in the TV series Vikings in which Ragnar Lothbrok assaults the city and takes it (Season 3) and Rollo later defends it (Season 4). The series is entertainment, not history, and so takes liberties with the known facts to achieve its ends. The raid led by Ragnar as depicted in the show has little in common with Reginherus' actual raid on Paris in 845 CE though elements of this raid were used in Season 3 when Ragnar's army acts as mercenaries for Princess Kwenthrith of Mercia and attacks the weaker Mercian army on one side of a river while the rest of the Mercian forces, on the other side, can only look on helplessly.

The dramatic scene in Season 3:10 where Ragnar feigns death, is brought inside the cathedral, and leaps from his coffin to kill the bishop is taken from legends concerning the Viking chief Hastein, who apparently employed this deceit at least twice. In the show, once the Vikings have won Paris, they return home but leave Rollo behind to secure a landing base for future raids; this leads to the historic offer the king makes to Rollo and his vassalage to Charles the Simple.

When Ragnar and his raiders return to Paris in Season 4, Rollo has built towers for defense and stretched a chain across the Seine. There was actually only one tower and, instead of a chain, a low-lying bridge. There is also no evidence that the Vikings in the raids of 845 CE or 885-886 CE dismantled their ships and carried them overland to come at the city from above; though it has been established that Vikings did do this at other times in other places for various reasons.

The depiction of Gisla and Odo in the show are largely fictionalized. Gisla was a young girl (perhaps even as young as five years) when she was betrothed to Rollo and so her courageous rallying of the troops during the siege never happened. Odo is depicted accurately only so far as his defense of the city; his relationship with Therese and plot to overthrow Charles, as well as the more lurid aspects of the TV character, are fictions.

For all its departures from fact, however, the series' depictions of the Viking raids on Paris provide an engaging slant on a fascinating time in the evolution of the French state. The treaty between Charles and Rollo established the first period of lasting peace since the Kingdom of West Francia was founded in 843 CE and provided the basis for a stable region. In time, and after further unrest, this stability would enable West Francia to prosper under the reign of Hugh Capet (987-996 CE) founder of the Kingdom of France, precursor to the modern nation.

Bibliography

- Brownworth. L. The Sea Wolves: A History of the Vikings. Crux Publishing Ltd, 2014.

- Collins, R. Early Medieval Europe, 300-1000. Palgrave, 2010.

- Ferguson, R. The Vikings: A History. Penguin Books, 2010.

- Hollister, C. W. Medieval Europe; A Short History. Wiley, 1968.

- Sawyer, P. The Oxford Illustrated History of the Vikings. Oxford University Press, 2001.

- Singman, J. L. The Middle Ages: Everyday Life in Medieval Europe. Sterling, 2013.

- Somerville, A. A. & McDonald, R. A. The Viking Age: A Reader. University of Toronto Press, Higher Education Division, 2014.

- Wolf, K. Viking Age: Everyday Life During the Extraordinary Era of the Norsemen. Sterling, 2013.

Translations

We want people all over the world to learn about history. Help us and translate this definition into another language! So far, we have translated it to: FrenchAbout the Author